Place: CBC Manitoba Broadcast Centre

Address: 541 - 543 Portage Avenue

Opened: March 14, 1927 (as Leonard and McLaughlin)

Cost: $200,000

Architect: Pratt and Ross

Contractor: J. McDiarmid Co.

Through the 1920s, Leonard and McLaughlin's showroom was located on Maryland Street between Portage Avenue and and Broadway. In 1926, it bought this property at 541 - 543 Portage Avenue which had been home to Central Tire and Vulcanizing / H. A. Fraser Tire Co. since 1910.

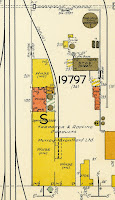

The new, two storey, 36,000 square foot showroom was built over the winter of 1926 - 1927. It stood 110 feet wide on Portage Avenue and 127 feet deep on Young Street.

The official opening took place on March 14, 1927 with Premier John Bracken in attendance.

May 9, 1931, Winnipeg Tribune

At the rear of the building on both floors were the service and repair shops. Much of the mechanical work was actually done on the second floor, an air exchange system ensured that exhaust was constantly drawn through vents in the ceiling. The service entrance off Young Street had a large elevator that brought cars up and down.

On June 10, 1932, W. L. McLaughlin died. In March 1939, Leonard and C. L. McLaughlin sold the company to F. Harris of Vancouver. Both men then retired to B.C..

November 27, 1940, Winnipeg Tribune

In 1940, Leonard and McLaughlin moved to new premises at both Portage Avenue at Maryland Street and Portage Avenue at Lipton. The military then leased this building for the remainder of World War II for the Mechanical Transport Wing of the Artillery Training Centre, where soldiers were taught to repair a wide variety of military vehicles.

April 27, 1946, Winnipeg Tribune

On May 1, 1946, Pigott Truck and Tractor Company Ltd. opened in this space. It was Winnipeg's exclusive GMC truck dealership and the Manitoba distributor for Allis-Chalmers tractors and heavy equipment.

Pigott's was run by three brothers. Ernest was president, Arthur the general manager and Norman the Secretary-Treasurer.

In March 1952, the Piggots sold the building and moved to larger premises at 1290 Main Street at Church Avenue. In 1954, they changed their name to Winnipeg Motor Products.

October 9, 1952, Winnipeg Free Press

The next owner of 541 Portage Avenue was the the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

At the time, their Winnipeg presence consisted of prairie regional offices and CBW radio studios located in the Manitoba Telephone System Building on Portage Avenue East. (This location was a holdover from the days when MTS owned the station, then known as CKY. CBC bought it out in 1948.)

Over $1 million was spent to transform the building into a broadcast centre.

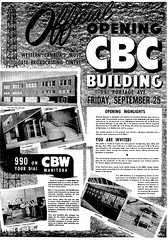

CBC Times, October 30, 1953

The exterior was resurfaced with Roman Brick, Tyndall stone and its columns in polished granite. The stone and granite continued through the font lobby. The lobby's spiral staircase appears to be original to the building, though the front entrance was moved to the east.

Inside, the floor was replaced with rubber tile and the space refashioned into offices and seven radio studios of varying sizes. The two-storey space that was once the service entrance with elevator was reserved for the main television studio.

A 250-foot tall transmission tower was added to the roof boosting CBW's power from 15,000 watts to 50,000 watts.

Top: Oct 18, 1953, CBC Times. Bottom: Sep 24, 1953, Winnipeg Free Press

The building was officially opened and the "new" CBW began broadcasting on September 25, 1953. Premier Douglas Campbell participated in the opening radio address which was carried across the entire CBC radio network.

The next phase in the building's redevelopment was to ready it for television. CBWT was to have been be the CBC's third television station after Montreal and Toronto, but equipment installation delays pushed the expected broadcast debut back a number of months allowing Vancouver to sneak ahead.

May 31, 1954, Winnipeg Free Press

Winnipeggers waited with great anticipation for their first local television broadcast slated for May 31, 1954. Some already had TV sets as signals from private broadcasters in North Dakota could often be picked up using antennae. For the vast majority of Winnipeggers, though, this would be a brand new experience. Furniture stores added televisions to their sales floors, some offered demonstrations and special training sessions. Eaton's went so far as to create an in-store closed-circuit TV station that alternated between pre-recorded short programs and live feeds from cameras overlooking Portage Avenue. This was broadcast to televisions set up around the store as an example of what TV would look like.

In late May 1954, there was a "television manufacturer's show" at the Winnipeg Auditorium where people could check out demonstrations of the latest models from companies like RCA, General Electric and Admiral.

Maurice Burchell, CBWT's first news announcer (source)

On May 24, 1954, six days before the first TV broadcast, CBWT began to transmit intermittent test signals which consisted of recorded video clips and a test pattern. Behind the scenes, Maurice Burchell, Winnipeg's first TV news announcer, and Ed Russenholt, the first TV weatherman, spent hours doing dry runs of their first show.

While the tests were going well, it was clear that Studio 41, being built in the former service garage area at the back of the building, would not be completed in time. This preempted any splashy local show on opening night.

June 2, 1954, Winnipeg Free Press

When CBWT went on the air at 8:00 p.m. on May 31, 1954 the 60,000 watt signal arrived sharp and clear well beyond its expected 80-mile radius.

The programming consisted of opening comments by Premier Campbell and CBC officials, including J. R. Findlay, director of the CBC's Prairie Region. Then it was local news and weather followed by a taped episode of the CBC variety show The Big Revue and episode one of Victory at Sea, an American made-for-TV documentary series. The Free Press declared the first night "a total success", though panned The Big Revue for being "not first-class entertainment".

Until the TV studio was completed in late June, the station filled most of its four-hour broadcast day with pre-recorded CBC programs and some American fare as CBWT was a secondary affiliate of American network CBS. By mid-July, 15 of the 85 shows aired on CBWT were locally produced.

CBWT aired both French and English programming until CBWFT began broadcasting on April 24, 1960.

Above: Tribune photo (source)

Below: CBC News Footage (source)

It didn't take long for the TV newsroom to get its "story of the decade". On June 8, 1954, the massive Time Building fire on Portage Avenue seriously damaged or destroyed five buildings. For the first time TV news cameras were on scene at such a disaster.

In 1955 it was the CBC building itself that became news when a local soft drink salesman on a dare climbed to the top of the building's transmission tower forcing the station off the air. A couple of thousand onlookers waited for the man to be coaxed down.

May 6, 1958, Winnipeg Free Press

In 1955, CBC acquired more land around the building and began construction of a two-storey addition for their television operations. Completed by 1957, it contained master control, transmission units, a film library, editing rooms and offices.

In 1957 CBW produced 1,594 hours of radio programming, CBWT produced 609 hours of television programming.

As the amount of programming increased and technology advanced, CBWT needed more space, especially a larger television studio.

In the mid 1960s the former Seventh Day Adventist Church at 355 Young Street, a few doors south of the main building, was transformed into a television studio. (The supper time news show 24Hours continued to be broadcast from there until the mid 1990s). A neighbouring apartment block was converted into office space.

In the years that followed, the church and apartment block was joined by a collection of temporary structures and trailers. The main building had not received any significant renovations or upgrade to much of its technical equipment since it opened. The union leveled official complaints that the complex was a "fire trap" and some employees were complaining about things like poor air circulation in the overcrowded conditions.

December 15, 1976, Winnipeg Free Press

In 1977 the CBC purchased the former St. Paul's College on Ellice Avenue and Vaughan Street and transferred it to the federal government. The idea was that it would become home to a new broadcast centre, but the five acre site was larger than it needed so the search was on for a partner.

Initially, it was thought that it could become home to a U of W field house, but university enrollment across the province was dropping and the likelihood of the province investing money in sports fields was unlikely.

The city wanted to see it used for housing - part of a downtown residential rejuvenation. That waned as the Core Area Initiative was formed and took on the redevelopment of the core of the city.

In the end, the federal government offered the partnership to the National Research Council for their new facility. Some thought this was a bad fit for he NRC as it was so far from research hubs at the University of Manitoba and Health Sciences Centre.

The early 1980s was the beginning of a recession and the CBC took major funding cuts as part of the federal government's belt-tightening. Their dream for a purpose-built Manitoba broadcast centre evaporated while the National Research Council's Institute for Biodiagnostics proceeded. (Two decades later, a second NRC building was built on the adjacent vacant land.)

It wasn't until February 1997 that a major renovation to the CBC's facilities was announced.

In early 1998, a $2.5 million building permit was issued. The most noticeable change was a new extension to the east of the original building that now houses the CBWT (television) news studio, the newsroom and the CBW (radio) studio.

Related:The heyday of CBC Manitoba's Studio 11

CBWT 35th Anniversary Look Back

CBC 75th Anniversary Blog cbc.ca

CBWT Canadian Communications Foundation

My other CBC posts:

Lloyd Robertson's Winnipeg Start

The CBC - Carman Air Disaster of 1952

My CBC Building gallery on Flickr

Source of 1980s building image from CBW souvenir booklet The Sound of Your Times Since 1948 (CBC).

Leftovers:

November 1929 ad

October 12, 1929, Winnipeg Tribune

(I couldn't find a follow-up story to see how he made out !)

January 30, 1946, Winnipeg Tribune

May 31, 1954, Winnipeg Free Press